We already see here, in the context of authentication, that there are multiple initiatives or systems already in place.

But there is a common challenge to overcome when connected to any of these portals: how can a citizen proof his or her legal identity, or, in other words, his or her age, when ordering a license or other official document?

This is where an electronic identity comes into play. A secure electronic method designed to prove a person’s identity and access digital services.

In Switzerland, such project started several years ago, and the journey, however, has not been without its hurdles. A significant turning point occurred when the initial e-ID Act faced a popular vote in March 2021 and was rejected by 64.4% of voters (1). This rejection was largely driven by public concerns regarding the involvement of private companies in managing sensitive personal data.

From this rejection, the Swiss government worked on a new project, learning from the previous concerns, and shifting to a state-controlled e-ID issuance and trusted infrastructure.

This revised approach is submitted to a public vote, scheduled for the 28th of September.

Before you continue reading, a little disclaimer: this post is not to expose or express the opinion of the author and is not aimed at convincing the readers to a position or the other. Rather, this post aims at giving information about how the e-ID works, from both a user perspective, and in the backend. Nevertheless, it will try to address some of the concerns that the public may have.

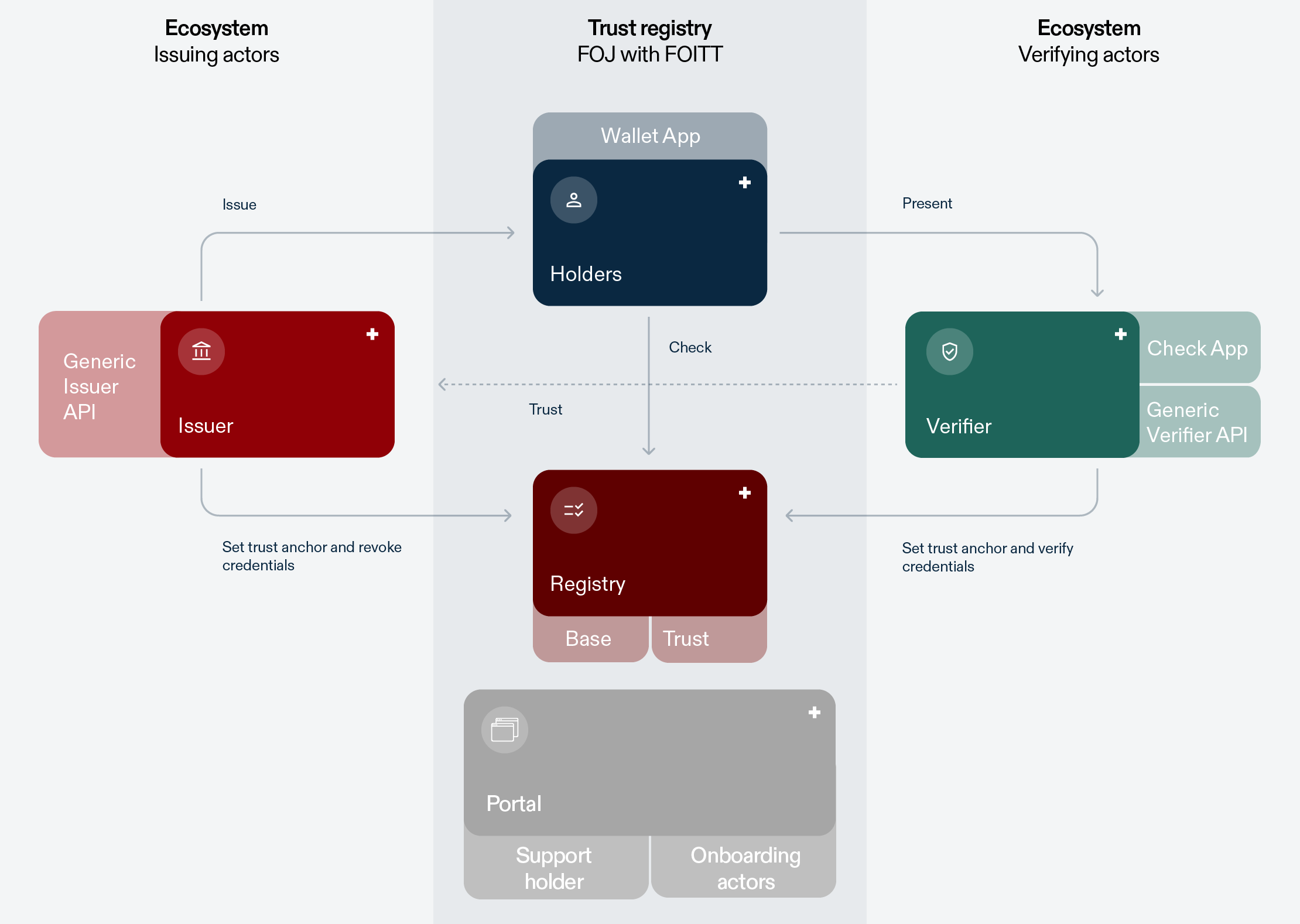

Defining Roles in the Swiss e-ID Ecosystem

(image from : https://swiyu-admin-ch.github.io/introduction/)

Firstly, the Confederation assumes the pivotal role as the sole issuer of the e-ID and is responsible for operating the secure trust infrastructure upon which the e-ID system is relying. The Confederation provides as well the “swiyu” wallet app, enabling users to manage their e-ID and other digital credentials (a credential is a fact about a subject, like the date of birth, the gender, or the AVS/OASI number). Indeed, it is planned that the “swiyu” app will also hold communal, cantonal, or even third party (private entities) credentials.

Beyond the central governmental role, Issuers are recognized entities, such as cantons, municipalities, or private companies operating under strict federal regulations, which can issue Verifiable Credentials (credentials that can be checked for validity) within the e-ID ecosystem.

In contrast, Verifiers, also known as Relying Parties, are service providers, whether public or private, that check the validity of credentials for authentication or data access. While they are not directly controlled by the government regarding the type of information they request, they are mandated to comply with data protection laws.

Last and far from being the least, the Users, comprising citizens and residents, can voluntarily apply for and use the e-ID free of charge. A cornerstone of the system is that users retain full control over their data, empowered to choose precisely what information they share through selective disclosure. In addition, the credentials will be stored in the hands of the users, namely the Identity wallet app, “swiyu”.

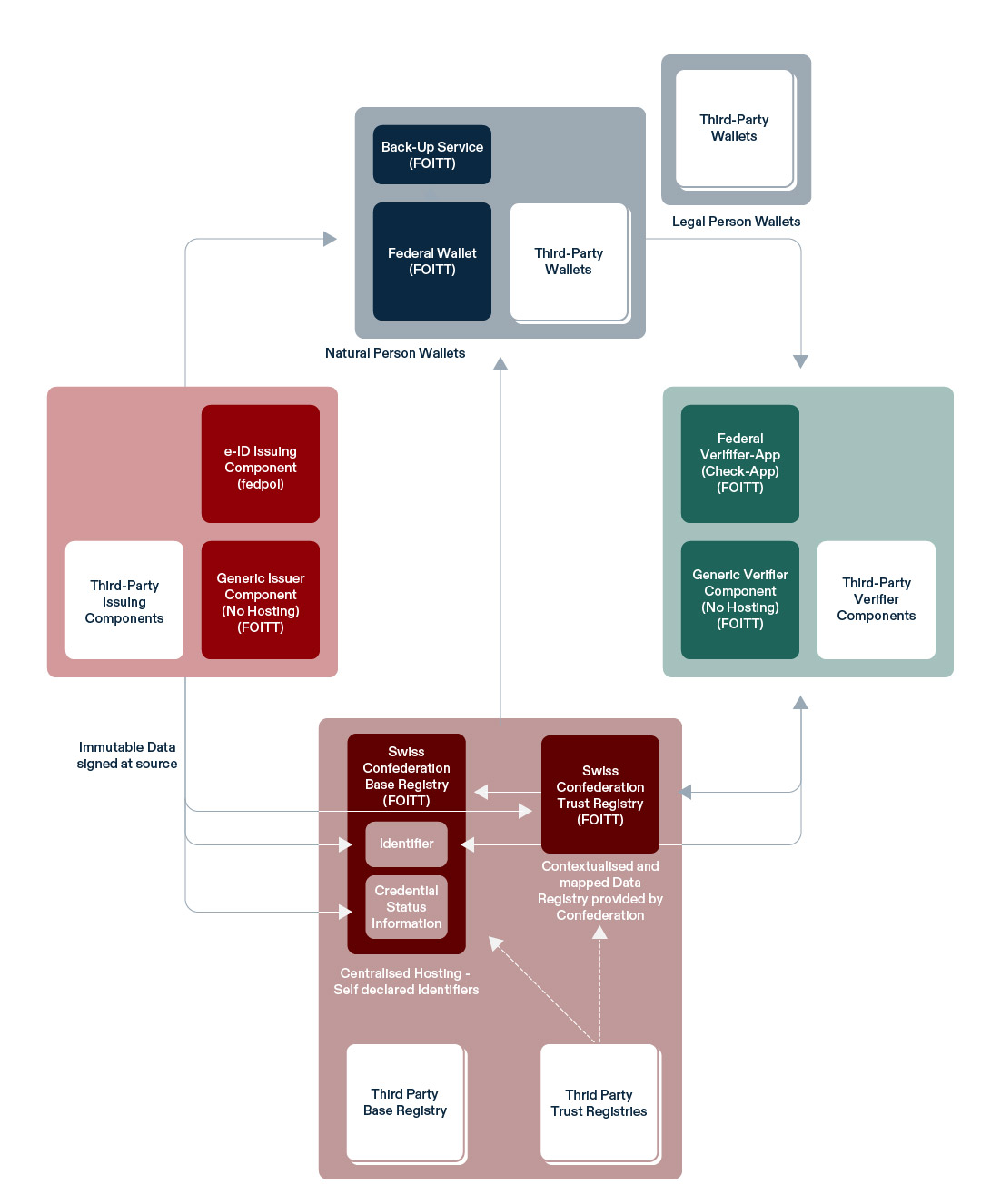

The Swiss Trust Infrastructure and Operational Flow

The Swiss e-ID is built upon the swiyu Trust Infrastructure, designed for the secure management of digital identities and credentials.

(image from : https://swiyu-admin-ch.github.io/introduction/)

The core components of this infrastructure include the swiyu Base Registry, which handles the public keys and manages the onboarding and offboarding processes for the issuers and verifiers entities.

In parallel, the swiyu Trust Registry stores and maintains the validity of the Base Registry identifiers, validated by the FOJ (Federal Office of Justice). For this, it stores the trust statement linking the technical identifiers with the legal entities in the real world.

The user interface is the swiyu Wallet App, a state-provided digital wallet where users securely store, manage, and utilize their e-ID and other verifiable credentials. To facilitate broad adoption and integration, the federal government also provides Generic Issuer and Generic Verifier Implementations, which are reference software for credential issuance and verification.

For the service provider to verify a credential, the swiyu Check mobile app, provided by the FOITT (Federal Office of Information Technology, Systems and Telecommunications), is used to verify the user’s credentials in the physical world (at a government office for example). Here, it is important to understand that the user is able to check the credentials that are being verified, and to choose whether he or she accepts to share these credentials with the verifier.

The e-ID infrastructure adopts the Privacy by Design (i.e. ensuring privacy at every stage of the design, development, deployment and operations) model, ensuring minimal data flows and decentralized data storage to safeguard personal information. Towards such model, a key concept is the separation of the technical identifiers in the Base Registry from the legal entity names in the Trust Registry, limiting the risk of data leaks in case of an incident.

Furthermore, credentials are device-bound, meaning they are tied to the user’s device to prevent unauthorized extraction and misuse.

Speaking about the operational flow, when a user wishes to authenticate with a service, the e-ID issues a one-time cryptographic token for that specific interaction, rather than sharing a reusable document. This drastically limits the system to track individual usages of the e-ID.

Some limitations

The first one is about unlinkability. In other words, to prevent the linking of different transactions performed with the e-ID, thus ensuring user activity cannot be traced across various services.

Another current challenge is the zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), that is being able to prove that a fact is true without disclosing the underlying data making this fact true. This requires advanced cryptographic tools, and, for example, enables verifiers to check an information (e.g., being over 18) without revealing the details like their exact age or birth date.

Analyzing Criticisms of the Swiss e-ID

And, the Confederation learned from this lesson, and largely addressed it in the law by making the Confederation responsible for issuance and infrastructure, thus correcting the previous approach.

We can’t agree more that it is a key advancement to make the project to be accepted by the citizens.

Another important concern is about privacy and surveillance. The critics come from a fear that a centralized identity system, no matter how well protected, could become a tool for surveillance or profiling by the government. This draws parallels to systems like China’s “social score”.

While the Swiss e-ID design targets for unlinkability (see above) and uses privacy by design concepts, officials state the government will not track individual usage. This concern is partially valid as a vigilance point.

The possibility of security risks and data breaches leading to hacking and identity theft is an inherent and valid concern for any digital system. Nowadays the risk already exists, with the increasing digitalization of the state and its affiliate organizations information systems. Think about the number of systems storing your AVS (OASI in English) number. Specifically to the e-ID, the Swiss government is responding by implementing robust security measures, including open-sourcing its code and planning a bug bounty program in 2025, to address these risks transparently.

Experiences made with the Covid-pass several years ago raise a concern about access to the state services in the future for citizens not having, or not willing to have, an e-ID. In the Covid times, both generational and technological barrier prevented people from going to restaurants or leisure services if they didn’t have the SwissCovid app on a mobile.

The LeID, and also the Federal Council in a dispatch of the November 22nd 2023, state that the use of the e-ID is not mandatory, free of charge, and that the service providers accepting the e-ID must also accept the physical IDs (ID card, passport, etc.). Detractors say, “for the time being”, but what about the future, where potentially service providers might eventually make it inconvenient to use traditional alternatives.

The final answer is unknown, but the concern about old-aged people or citizens who are not technology savvy and therefore hindered from accessing digital service would likely not be in the best means even without the e-ID, thus not a huge concern.

This is a valid practical concern the government must continually address through inclusive access strategies and by ensuring that traditional identity methods remain viable and accessible for all citizens.

Finally, skepticism exists regarding the government’s IT competence in managing complex digital projects. Historically, several government IT projects have faced challenges.

For this, Beat Jens, heading the department implementing the e-ID, responded recently that the e-ID project is in good progress, and is going to be delivered on time and in budget, expecting the e-ID to be available 1 year after the poll.

Other Digital ID Implementations

As introduced at the beginning of this post, numerous countries have implemented or are developing their own digital ID systems, each with different characteristics.

For instance, Estonia launched its digital ID infrastructure in 2002. It revolves around a mandatory digital ID card using Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) technology, allowing secure authentication and digital signatures. It has been made mandatory to all Estonians to have such digital ID.

In contrast with Switzerland, Sweden‘s BankID, launched in 2003, is primarily a private-sector initiative built through a consortium of banks.

In Germany, the government introduced electronic ID cards in 2010, including a chip storing personal information and biometric data. It can be used on government portals, tax filing, and digital document signing. While designed for interoperability, it has faced challenges related to complexity and public awareness.

Outside the European continent, India‘s Aadhaar system, launched in 2009, is a massive undertaking serving 1.3 billion citizens. It assigns a unique 12-digit identification number based on biometric and demographic data. It is highly centralized which raises significant privacy concerns.

Conclusion

The Swiss e-ID project marks a significant step toward digitalizing public services and enhancing interactions for its citizens. By integrating lessons from the 2021 referendum and firmly rooting the project in state control, privacy-by-design principles, and through open-source, Switzerland aims at proposing a robust and trusted digital identity system. And this, despite the legitimate concerns regarding privacy, security, and universal access.

Hopefully, this blog post showed how the Swiss e-ID works, its potential weakness and concerns while trying to give answers to them.

0 Comments